Outside of watching movies like Don’t Look Up or Armageddon, most of us don’t think much about the possibility of an asteroid or a comet slamming into Earth and ending (or at least upending) life as we know it. But some astronomers think about it day in and day out, and have dedicated their careers to making sure it doesn’t happen. From simulating an asteroid impact to actually crashing a spacecraft into an asteroid, NASA’s all over it—and just upped its asteroid-impact-prevention game even more.

The space agency funds a program called ATLAS, which stands for Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System. Developed by the University of Hawaii, ATLAS consisted of two telescopes in Hawaii that would scan the sky over the northern hemisphere in search of near-Earth objects. This week NASA announced that ATLAS got two new telescopes—one in Chile and one in South Africa—that now enable it to do “full sky” searches.

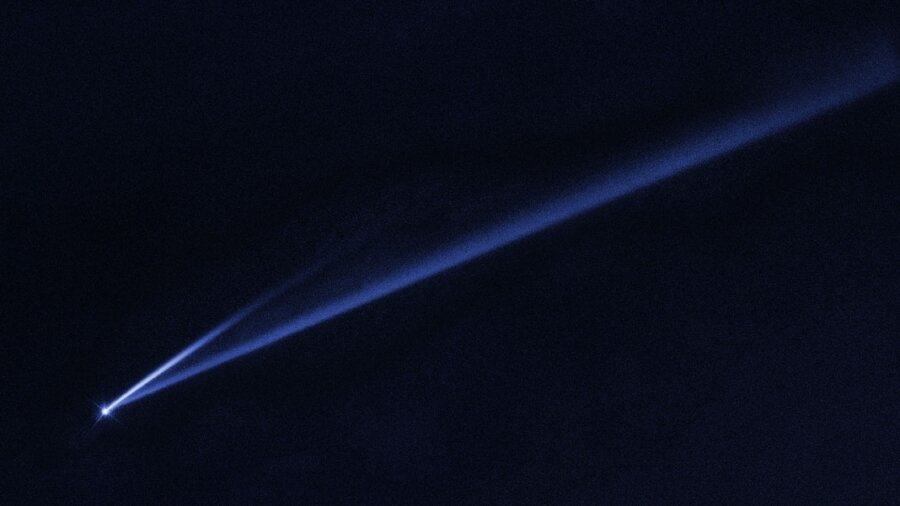

The original two telescopes in Hawaii have been operational since 2017, and since then ATLAS has spotted more than 66 comets and 700 near-Earth asteroids (two of which actually hit Earth’s atmosphere! But they were tiny and didn’t do any damage). The Chile and South Africa telescopes allow ATLAS to survey the night sky when it’s daytime in the northern hemisphere, substantially increasing the system’s visibility.

“With the addition of these two telescopes, ATLAS is now capable of searching the entire dark sky every 24 hours, making it an important asset for NASA’s continuous effort to find, track, and monitor NEOs,” said Kelly Fast, Near-Earth Object Observations Program Manager for NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office.

ATLAS is designed to detect objects that get closer to Earth than the distance to the moon; that’s a range of about 240,000 miles (384,000 kilometers). If that sounds pretty far away, consider the fact that near-Earth objects are defined as asteroids or comets that come within 27.9 million miles (45 million kilometers) of Earth’s orbit. Seems the word ‘near’ is pretty loosely used in this case—though to be fair, that distance is no more than a stone’s throw when taken in the context of the entire galaxy.

ATLAS can spot small asteroids (20 meters wide or smaller) within several days of potential collision with Earth, while larger asteroids (100 meters wide or more) are visible weeks before they’d impact Earth. And the system’s findings aren’t just for NASA; ATLAS sends data on its observations of the night sky to the Minor Planet Center, where it’s accessible to astronomers from all over the world. They can use the data as a starting point to gather more information, like calculating objects’ orbits and figuring out whether they pose any danger to us.

On the whole, the threat of the world being destroyed by giant objects flying through space is low, and let’s face it—we have plenty of bigger fish to fry. But if it ever does happen, NASA’s seeing to it that we’ll be ready.

“We have not yet found any significant asteroid impact threat to Earth, but we continue to search for that sizable population we know is still to be found,” said Lindley Johnson, planetary defense officer at NASA headquarters. “Our goal is to find any possible impact years to decades in advance so it can be deflected with a capability using technology we already have.”

Image Credit: NASA

* This article was originally published at Singularity Hub

0 Comments