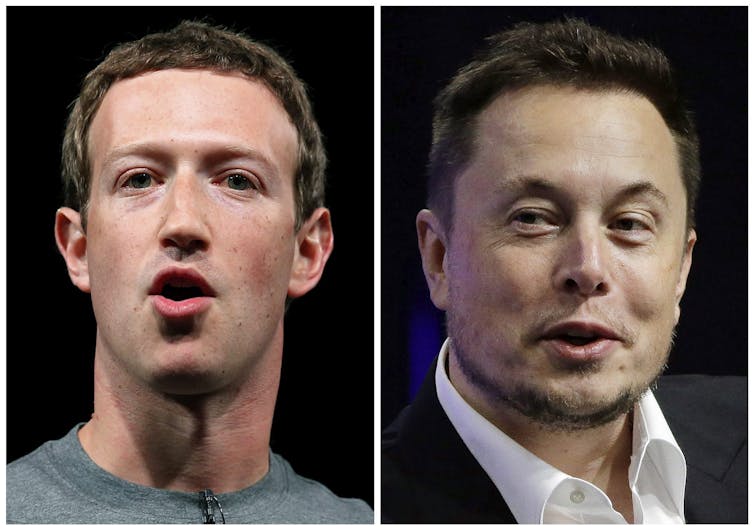

The July 5 launch of Threads, Instagram’s new social media platform, has met with considerable interest. Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg was quick to report that over 100 million users downloaded the app by the end of its first weekend.

The apparent success of Threads stands in stark contrast to other recent social media apps such as Spill, Bluesky, Mastodon and others.

Although Threads has been called the fastest growing app in history, it remains to be seen whether interest will be sustained over the long run.

Threads’ success is by no means assured. The app doesn’t present a radical departure from Twitter’s formula, doesn’t have access to the European market due to privacy concerns, and faces a potential lawsuit from Twitter which has also introduced revenue sharing to verified users.

The success of Threads is perhaps less about the features of the app than the recent decisions made by Twitter owner and CTO Elon Musk. Accusations of censorship, self promotion and continued negative cashflow have created an undeniable window of opportunity for would-be challengers.

Unlike Twitter’s other rivals, Meta’s already expansive user base with nearly three billion users means that the curiosity of a small number will allow it to quickly bypass other startups.

Its success will ultimately rest on whether it creates a sustainable niche for itself in the marketplace.

A complicated process

Many technologies are branded as ‘innovations’ without any qualification. Innovation is a process, and one that is defined by showing not telling. Even if a product or idea is novel, if it’s not widely adopted, it does not truly represent an innovation.

Innovation is best understood as an evolutionary process, defined by three features: replication, variation and selection. If an idea works, duplicating it should lead to success.

But blindly copying someone else’s idea, concept or technology is insufficient. Often, the context for replicating ideas typically differs from one situation to the next — if only slightly. Local resources, funding, values and attitudes must be considered. If innovators ignore these differences, novel procedures, products and services will not spread.

Where innovation is ultimately demonstrated is through selection, which can be a conscious or unconscious process. Unconscious adoption involves blind mimicry, with people copying their peers or those with high status. Conscious adoption involves understanding what a technology can and cannot do. This requires more knowledge and time.

The outcome of the selection is the creation of a niche, a segment of the social and physical environment. When a product is selected, it is because it fulfils some niche in a market. But that niche might already be occupied.

Common threads

Threads is inspired by Twitter and replicates some of its features. But Threads’ rapid adoption suggests that it fulfils a niche.

Twitter was launched in July 2006, nearly two decades before Threads. However, Musk’s recent changes to Twitter created space in that niche.

Musk is purportedly a champion of free speech. While his early reinstatement of previously banned users might suggest this, he has gone on to selectively ban those who questioned him and appointed himself as an arbiter of content, claiming that Twitter will treat the term “cisgender” as a slur.

Some have speculated that the catalyst for the release of Threads was Twitter’s recent decision to throttle — or limit access to — posts. Following its launch, Threads was also forced to impose such limits, citing spam attacks.

There is a history of technological niches creation and competition. In the decade-long smartphone wars, Apple sued Samsung for “blatant copying.” Samsung counter-sued Apple, and Nokia followed suit. Apple also sued Microsoft over allegedly copying display elements. And Chinese technology firms have historically been notorious for copying the products of other companies.

While innovators and firms can create a niche, they open the door for other variants.

Old problems, new threads?

A major selling point for Threads is that it wants to avoid the divisive politics that have made social media a caustic, polarized environment. It is not clear how this can be accomplished in practice, as content moderation is exceedingly difficult.

While content moderation seems like a reasonable solution to the ills of social media, it faces many problems.

The debates — and tensions — associated with free speech, cannot be solved by the intentions or actions of any one company, industry leader or government.

A continuing thread

It is unlikely that Twitter will go the way of ossified social media platforms like MySpace any time soon.

For the foreseeable future, competition between the social media giants will prevail, with each defined by its own market share. Indeed, Instagram’s CEO noted that “the goal is not to replace Twitter.”

What is left unaddressed in this debate is whether or not social media in its current form is beneficial for society.

Greater care must be taken to ensure that the social and ethical implications of these technologies are part of the adoption process by individuals and society.

Jordan Richard Schoenherr does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

* This article was originally published at The Conversation

0 Comments