Nuclear fusion has experienced something of a renaissance in recent years with a host of startups and governments seriously pursuing the idea. UK scientists have now provided a sneak peek of a novel reactor design that could be providing power to the grid by 2040.

Despite a reputation for being a technology that’s always 20 years away, recent years have seen a flurry of investment as optimism grows that its time may finally have come. According to the Fusion Industry Association, last year’s $900 million in new funding brought the total to $7.1 billion.

That optimism doesn’t seem to have been dampened by major delays to ITER, the international collaboration that has long been considered fusion’s flagship project. Building on the knowledge gleaned from ITER and other publicly funded experiments, a host of startups is now betting they can deliver smaller fusion reactors at a fraction of the time and cost.

But it’s not only the private sector pushing to commercialize the technology. In 2019, the UK government provided £300 million in funding for the design of a novel 200-megawatt reactor known as Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production (STEP). And in a series of papers recently published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, its designers have now given a glimpse of what they’ve come up with.

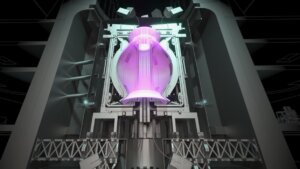

The most common design for a fusion reactor is known as a tokamak, which heats a cloud of ionized gas, known as plasma, until the atoms fuse together and generate huge amounts of energy in the process. The plasma is contained by incredibly strong magnetic fields generated by coils of magnets wrapped around a doughnut-shaped reactor vessel.

STEP follows similar principles but is tall and narrow, more like a cored apple, according to Science. While that might not seem like much of a difference, it means the distance between the center of the reactor vessel and the magnets wrapping around it is smaller than a classic tokamak.

This reduction in distance makes it possible to use smaller, less expensive magnets to contain the plasma and makes the entire design more compact, according to the Financial Times. The shape of a spherical tokamak also produces an inherently more stable plasma, which should improve performance. However, the design does have trade-offs.

Fusion reactors normally use two isotopes of hydrogen fuel called deuterium and tritium. Tritium is incredibly rare though, so reactors generate their own tritium by way of a reaction between the metal lithium and neutrons released by the fusion reaction. This lithium is stored in tritium breeding blankets wrapped around the chamber, which also act as radiation shields to protect the magnets.

The hole in the center of a tokamak normally houses large magnets and a breeding blanket. But with the narrower design of the spherical tokamak there is much less space, so the STEP reactor will have to do away with the blanket and significantly shrink the magnets, or even do away with some.

Fortunately, new high-temperature superconducting tape, which is also being used by many private startups, could help create more compact magnets. But the reactor will have to generate enough tritium using only the blankets on the outer wall of the chamber, which means the team had to come up with an optimized design using liquid lithium and a vanadium alloy.

The reactor’s designers have also opted for an ambitious architecture with joints in the magnets, which will make it possible to open the top of the vessel. This will significantly speed up maintenance jobs and therefore lower operational costs.

However, project leader Paul Methven, told Science that the recently published designs are still far from being set in stone. And while the project has already found itself a site—a retired coal-fired power station in Nottinghamshire county—the project is currently in discussions with the UK government to secure four more years of funding to come up with a final blueprint.

So, whether or not this reactor ever sees the light of day remains to be seen. But it’s encouraging to see government investing significant sums to push the technology forward.

Image Credit: STEP

* This article was originally published at Singularity Hub

0 Comments