Technology is so ingrained in our lives that most children today are “digital natives”. Indeed, they might “speak” digital before they even learn a language, and digital natives are often asked to educate older “digital immigrants”, such as their parents, about how to use technology.

At the same time, a great many parents are concerned about the potential harms of exposing their kids to technology, screens, and the internet in particular.

Studies have shown that digital technology has a range of effects on children. These can be very positive, such as children being able to grasp mathematical concepts or understand languages much earlier than their millennial counterparts. They can also be negative, such as increased levels of depression from excessive or compulsive social media use, cyberbullying, and being manipulated by strangers online.

In order to understand the effects of technology on young people, our research has built a tool that measures children’s “digital maturity”. It marks an important step in deepening understanding of how technology affects children’s development on a psychological, academic and holistic level.

Our Digital Maturity Index was developed alongside researchers from across the EU under the EU-funded Digymatex project. This metric assesses how developed or advanced a child’s relationship to technology is, as well as what it means for their overall development.

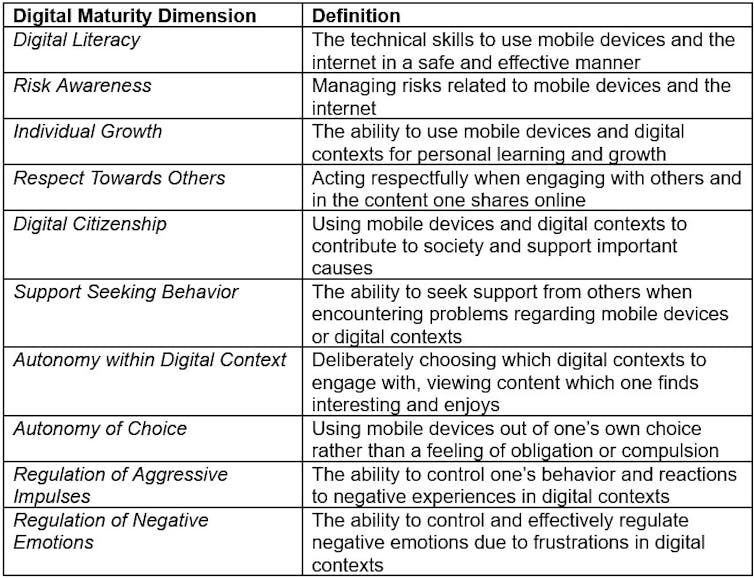

The Digital Maturity Index is comprised of a set of dimensions or components that, when taken together, offer a holistic overview of how mature a child’s relationship with technology and the internet is. The components are digital literacy, risk awareness, individual growth, respect towards others, digital citizenship, support seeking behaviour, autonomy within digital context, autonomy of choice, regulation of aggressive impulses, and regulation of negative emotions.

Real-world applications

The index is, in and of itself, a very helpful way for parents, educators and child psychologists to quantify the impacts of technology and internet exposure on a child. However, our objective was to build a tool that could help them to not only assess a child’s digital maturity, but also to design targeted interventions.

To do this, we first used the index to gather data from 1,440 respondents in Austria, Denmark, Germany and Greece. We then used machine learning to analyse the data and categorise children into types of digital maturity. We found that children consistently tend to be clustered into three groups: low, medium, and high digital maturity.

Not surprisingly, being in the high digital maturity category was positively associated with high digital literacy, awareness of the risks of browsing the internet, use of technology for personal growth, and non-compulsive browsing behavior. This category was the least concerning for parents and educators, and it serves as a reference point, the “best case scenario” of children’s online behaviour.

Children in the medium category exhibit low compulsive behaviour, but they do not acknowledge the use of technology for personal growth, and show medium to low digital literacy. The low category includes children with very high compulsive behaviour, very poor risk awareness, and poor regulation of negative emotions.

Understanding the children that belong in the two lowest categories is vital for educators and psychologists, as they can develop targeted interventions aiming to improve those specific areas that the children seem to be lacking.

Country-specific trends

Interestingly, our data showed that digital maturity patterns varied widely across countries. We noted several interesting differences.

Children in the low digital maturity category in Germany and Greece shared broadly similar patterns. They scored below average in nearly all dimensions, including impulsive behaviour and emotional regulation, but German children in this group exhibited particularly low scores in Digital Literacy (such as understanding privacy settings) and Risk Awareness (such as identifying online dangers). Greek children, on the other hand, demonstrated slightly stronger Autonomy Within Digital Context, despite struggles with compulsive device use.

Meanwhile, Austrian children with low digital maturity stood out for scoring above average in Digital Citizenship, a unique trait not observed in other countries’ low-maturity clusters.

In addition, children with low digital maturity broadly showed low Autonomy within Digital Contexts in all other countries besides Denmark, where this group scored much higher in this category.

Another interesting observation is that the high digital maturity group shows high Autonomy of Choice in all countries except Germany, where this dimension is slightly below average for children in the high-scoring category.

A tool for parents, educators and researchers

Beyond understanding the categories of children with regard to their digital maturity, we have developed a prediction tool that, using machine learning, allows users to assess a child’s digital maturity.

Using our algorithm, users can answer a set of questions about a child’s behaviour, and receive an estimate of their digital maturity level, as well as indications about areas for improvement.

Our aim throughout this endeavour was to create a platform that can help researchers as well as parents, educators, and child psychologists to better understand the impact of technology on children. If used appropriately, it can help caregivers to make informed decisions that encourage children to develop and maintain healthy digital habits.

Konstantina Valogianni receives funding from EU H2020 Program and IE Business School.

Aqib Siddiqui received funding from EU H2020 Program and IE Business School.

* This article was originally published at The Conversation

0 Comments